Thursday, October 12, 2006

Emilia-Romagna Into the Nano-Age Through New Public/Private Partnerships

Emilia-Romagna is a highly industrialized region in north-central Italy of about 4 million residents.

Manufacturing has provided Emilia-Romagna's citizens with high wages and standard of living, and sustained economic growth. Faced with increased global competition, the Emilian economy has responded creatively and aggressively, actually increasing employment in manufacturing over the last 10 years.

A key factor in the success of manufacturing has been active government policy in support of business growth, cluster development, and building effective links between applied research and advanced manufacturing.

In December 2004, the region's government announced the creation of the Regional Network for Industrial Research and Technology Transfer, made up of 27 Industrial Research and Technology Transfer Laboratories, 24 Innovation Centers and 6 Innovation Parks.

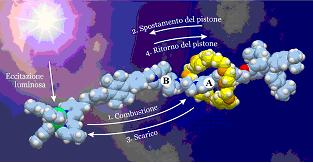

Researchers in this network have recently invented a solar-powered “nano-engine.” The size of two molecules, this new motor is as fast as a normal four-stroke engine spinning at 60,000 RPMs with potential applications in medicine, computers and manufacturing. And it's solar-powed to!

Development of this new technology has been turned over to the regional laboratory, Nanofaber. Nanofaber is a public-private partnership (a 'networked' lab) among the regional government, several public research institutes, the University of Bologna, and a group of regionally-based manufacturing firms, including SACMI a leading worker-owned cooperative.

Nanofaber's mission is to develop and commercialize this technology to the benefit of the region's clusters of small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

The nano-motor is just one of the fruits of the region's new industrial innovation policy designed, in the word's of Minister of Development Duccio Campagnoli, to ensure the regional economy's competitiveness for the next forty years.

You can read more about 'Sunny,' as the nano-motor is nicknamed , in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Cooperativa CEFLA of Imola

I went to the dentist for the first time in four years last week.

My excuse for not having gone more frequently was that I was living in Italy.

Upon hearing this, my dentist mentioned that Italy is producing some of the best, most elegantly designed dental equipment and materials in the world.

On a whim, I asked if he'd ever heard of Anthos, the brand-name of one of the Imolan cooperatives.

Last year, towards the end of my stint in Emilia-Romagna, I had the pleasure of interviewing Claudio Casini, the president of one of Imola's largest cooperatives CEFLA.

Imola is a small town of about 60,000 people just outside of Bologna. Imola is the heart of the Italian cooperative movement. Among this small town's 100 or so cooperatives, are the largest, oldest and most successful worker-owned cooperatives in Italy--indeed in the world.

We'll here more about Imola in future posts. Back to CEFLA.

CEFLA was started in 1932, at the height of Italian Fascism by a group of unemployed anarchists and socialists branded "subversives" by the Regime. Unemployment in Imola at the time was around 20%

The original co-op was started by nine members. CEFLA stood for Cooperative of Electricians, Fountain Attendants, Tinsmiths and Related.

The co-op was headquarted in the storefront of one of the members. The co-op specialized in producing and installing heating systems, plumbing and electrical wiring. The co-op's first significant contract was the installation of a heating system in a local hospital.

Today, the CEFLA Group employs just over 1,000 people, with 273 worker-owners. The group has annual revenues of about 200 million euros, 90 million from exports. They still do heating and electrical installation, but have since expanded to include several divisions:

1) Retail shopfitting

2) Dental equipment

3) Automatic wood varnishing machinery

4) Heating and electrical installation

You may not know the name CEFLA, but you may know some of their brands: Duspohl, Delle Vedove, Falcioni, Sorbini, Zenith, Ariam, Anthos, Sternweber, Elca and Dna-Anthos.

CEFLA is unique in many ways.

Like many other cooperatives in Imola, they have expanded through aquisition of companies in crisis (including the cooperative CIR). Typically, the cooperative sets up a holding company and creates a hierarchical relationship: members in the 'mother firm' and subsidiaries subordinate to the mother firm.

Not so with CEFLA. Here, the aquired companies aren't set up as subsidiaries of the cooperative, but as divisions of the cooperative, with members placed strategically in each of the divisions.

This makes good business and social sense: since it's unlikely that each of the markets the co-op sells to will experience downturns at the same time, members and employees can be shifted from one division to another when there is a slump in a particular market. CEFLA has never had a layoff. In fact, they were able to absorb a good portion of the members and employees from another local co-op that went belly-up in the 1980s.

All of the co-ops I interviewed invest a significant portion of annual profits into an "indivisible fund" which they don't pay taxes on, but can never payout to members. The indivisible fund can only be used to grow the cooperative. These retained earnings, unlike in a private firm, don't increase shareholders' equity--it's money that belongs to "future generations."

CEFLA is unique in this respect too: not only do they invest a majority of profits each year into these indivisible reserves--according to company regulations, the members had to invest enough profit into the firm each year to grow the indivisible reserves by at least one percentage point above inflation. Additionally, the amount that members could earn (the sum of salary + interest + patronage dividends) was capped at an amount lower than that allowed by law.

Finally, CEFLA is unique in another aspect. Despite high rates of unionization (and historical ideological ties) relations between the cooperative movement and the labor movement have chilled. The co-ops generally think the unions just don't get it. "They want to reproduce the same conflict between capital and labor you have with private firms" is something I've heard many times. The unions are equally critical of a cooperative movement they say has lost sight of its original values under market-pressures to be competitive.

Despite this, CEFLA makes a point each year of meeting with the labor movement to discuss the annual budget in the spirit of transparency and participation.

So what does this have to do with my dentist?

This aggressive reinvestment of profit back into the company is a big part of why this small, worker-owned firm from Imola is now a global leader in -- among other things -- the development and production of cutting-edge dental equipment.

So, when I asked my Dentist if he knew "Anthos." He said: "I'm pretty sure they're the leader in the new digital x-ray technology that all the dental offices will be using in five years. "

In my conversation with Casini, he made a point of talking about their dental division. This was perhaps where they were implementing their boldest strategy yet: major investments in R&D to develop the next generation in dental technology so that they could break into the American market, where their biggest competitor is the multi-national GE.

Looks like their strategy is paying off.

But I think the competitive advantage of the co-ops can't be accounted for simply in terms of investment in R&D or other aspects of the business model.

I have to agree with Casini, who told me:

"Un'impresa senza valori sociali ha le gambe corte."

That means: a business without a grounding in social values ain't going very far.

I asked him to clarify, and he said it unequivocally: "our values are our competitve advantage."

Friday, October 06, 2006

By Way of Introduction

By Way of IntroductionFor two-and-a-half years, from August 2003 to December 2005, I was immersed in what is one of the most important and large-scale experiments in economic democracy in an advanced industrial society.

In the spring of ’03, while working at my current employer the Center for Labor and Community Research, I expressed interest in going back to Italy to go to grad school. Dan Swinney, CLCR’s Executive Director, suggested focusing on Bologna.

Bologna is the capital of Emilia-Romagna, Italy's most prosperous and economically dynamic region. Emilia-Romagna—with it's left governments, vibrant network of small firms cooperating and competing in flexible networks, and perhaps the world's strongest cooperative movement—was an important model of democratic, sustainable development and high performance economics.

Emilia-Romagna, along with Mondragon, Spain, are two international examples that had inspired CLCR’s work and that we needed to gain a deeper understanding of.

In August 2003 I left Chicago for Bologna, armed only with a guide to the history of Emilia-Romagna and two contacts: Francesco Garibaldo of the region's Institute for Labor and Professor Stefano Zamagni, leading academic in the civil economy and director of the University of Bologna Master's Degree in Cooperative Economics.

I spent my first year working as a researcher at the Institute for Labour, doing work mostly in the private sector, studying flexible networks of small and medium enterprises.

The Institute for Labour is a research institute, founded and partly funded by the regional administration, that works with business and labor to implement high road, participatory forms of work organization. Working at the Institute for Labor I was able to gain first-hand knowledge of the regional development model through meetings with labor leaders, entrepreneurs and managers, as well as key policy makers.

In September 2004 I enrolled in the Master's Degree in Cooperative Economics, studying the cooperative movement with Italy's top cooperative managers and academics. Essentially a ‘cooperative’ MBA.

Thanks to my experiences at the Institute for Labor and in the Master's program I was able to have an intimate, 'insider's view' of this extremely complex, dynamic and economically vibrant system based largely on worker ownership. Often the cooperatives—as is the case in manufacturing, construction, services, farming and retail—are among the market leaders in Italy, and the largest firms in the region. Many of the region's large manufacturing coops are leaders globally in their field as well.

What I discovered in my two-and-a-half years there—through interviews with top policymakers, labor, business and the cooperative movement—is a world-class model for sustainable development, one that combines the market, participatory planning and economic democracy.

This Blog will be a collection of my thoughts and writing about Emilia-Romagna, as well as up-to-date analysis of changes in the regional economy, in policy and in the cooperative and labor movements. I hope it can become a real resource.

I’m very thankful to my good friend Dan Bianchi who’s in Spain right now studying in that other center of economic democracy and High Road economics, Mondragon. He really pushed me to start this blog and put my thoughts down on paper.

I was also extremely lucky to have benefited from the support of Bob Williams of the VanCity Credit Union in Vancouver. Without their generosity, I would have been giving English lessons and not studying this wonderful region’s economy, politics and society.